David L. Stanley

Late Night Thoughts About the 2023 Tour de France

David Stanley is an experienced cycling writer. His work has appeared in Velo, Velo-news.com, Road, Peloton, and the late, lamented Bicycle Guide (my favorite all-time cycling magazine). Here's his Facebook page. He is also a highly regarded voice artist with many audiobooks to his credit, including McGann Publishing's The Story of the Tour de France and Cycling Heroes.

David L. Stanley

David L. Stanley's masterful telling of his bout with skin cancer Melanoma: It Started with a Freckle is available in print, Kindle eBook and audiobook versions, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

David L. Stanley writes:

The 2023 Tour de France ended Sunday around 1:00 pm EDT. At 2:00 pm, I sat down with my three Feed-Zone podcast brothers (brought to you on the Cycling Legends podcast network, and yes, I mention BikeRaceInfo.com just as much on the podcast) to discuss the stories behind the stories (and all the inherent digressions therein) for 90 minutes. But come the middle of the night after the last day, I always wake up after a few hours of sleep with a handful of burning questions and thoughts about the Tour just ended. Herewith, nine questions that kept me up on Sunday night. It’s alphabetical, and as always, no wagering.

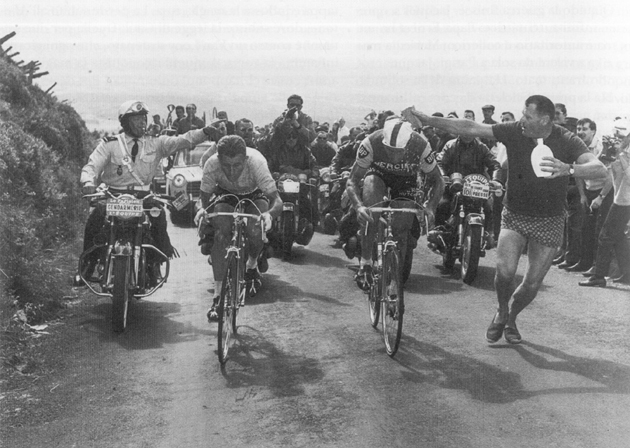

Collegiality. Fausto Coppi vs. Gino Bartali. Raymond Poulidor vs. Jacques Anquetil. Eddy Merckx vs. Luis Ocaña. Jeanie Longo vs. Maria Canins. Greg LeMond vs. Bernard Hinault. Bradley Wiggins vs. Chris Froome. Cycling, like every combat sport, is filled with conflict. Conflict can turn to nasty rivalries on and off the bike. It’s rare that sportspeople at the very top of the sport are anything other than nodding in their respect for their toughest competitor, Federer vs Nadal as an exception. Cycling books have been written about the greatest rivalries in the sport. Those rivalries are nasty, brutish, and in many instances, life-long on and off the bike.

1964 Tour de France, stage 20: Anquetil and Poulidor in their famous race up Puy de Dôme. Anquetil narrowly saved his lead.

But in these otherwise troubled times, we have Jonas vs TaddyP shaking hands at the beginning of every stage, fist bumping and the occasional hug at the end of a stage, shared laughs, and assorted other signs of brotherhood. Importantly, that collegial behavior has filtered down through the rest of the peloton, Jasper Philipsen antics aside.

Vingegaard (in white) & Pogacar after stage 18 of the 2021 Tour. They have been collegial rivals for a while. Sirotti photo

I have the impression that consciously or not, the two kings of cycling both realize that they are doing something very special, that without the quality and presence of the other, the success they’ve both enjoyed in the last two Tours would mean less. Moreover, it would not be nearly so breath-taking. These two are driving each other to levels of success we have not seen in 35 or 40 years. These two guys really like racing bikes as hard as humans can race.

Combativity jersey. In every Grand Tour, there are guys who bust themselves to get into every move. They attack and attack and attack. Some attacks stick, far more are reeled in, and still the guys, think Jens Voigt and Victor Campanaerts, go on the attack the next day. There is an award, a red colored race number, and a small cash prize awarded each day. That’s not enough.

With each day’s stage, the racing starts for real at kilometer zero. No more lollygagging for the first 50 or 70 km. The flag drops. The racing starts. Let’s come up with an algorithm for calculating combatif points, find a sponsor, and award a real jersey every day just as we do with the yellow, green, white, and polka dots. Those combatif riders enliven the hell out of every stage. Time to reward them. Maybe get Stanley Tools (no relation) to sponsor the jersey. The markings on the Maillot Combatif? A hammer, d’accord?

Thibaut Pinot gets the combativity award after stage 20. Sirotti photo

Equipment fails. Never in the history of the Tour have so many chains broken during the day’s stages. Every stage, we saw men standing by the side of the road with chain-less bikes, and not the sort where a belt-drive is present. Memo to Shimano, Campagnolo, and SRAM. Just because you can cram 12 cogs onto the rear hub, and thin a chain down to a razor’s edge, that doesn’t make it a good idea. Stop it.

Nils Politt with a broken chain in stage 19.

Mohorič. Matej Mohorič rides for Bahrain Victorious. Gino Mader did, too. The 26 year old Mader died on June 16 after a crash during the Tour de Suisse. Matej has won stages in all three Grand Tours. He has won a Monument: Milan-San Remo. He won stage 19 of the Tour de France for Gino Mader. Please watch this interview with him. Hemingway said, “Write the truest sentence you know.” This interview, right after his stage 19 win, is the truest sentence(s) ever written about the Tour de France. [CLICK HERE for the interview]. There is nothing more to say, eh?

Matej Mohorič's stage 19 win.

Packfiller. (with a tip of the hat to my friend and colleague Patrick Bulger, the original Packfiller. ) Packfiller refers to those riders who crush themselves every day and are the mainstays of the peloton, but are rarely celebrated and almost never win. This year’s Tour started with 176 riders. 150 racers finished. Michael Morkov (Soudal Quick-step) was this year’s Lanterne Rouge. He finished 6 hours and 7 minutes behind Jonas Vingegaard. He did his jobs every day; to look after his team leader, to lead out his man for the sprints (he is best lead-out man in the world), to chase down disadvantageous moves, and to get over the mountains as best he could. In addition, Morkov is one of finest track cyclists in the world and the holder of a variety of world championships.

Pierre LaTour (TotalEnergies) finished 75th, dead center of the final GC. In 2018, LaTour won the best young rider competition in the Tour de France. He won a stage of the Vuelta. He is a two-time French time trial champion. An exceptional climber, he was the second man to the top of the Puy de Dôme. He is still in recovery after a horrible crash in the Tour of Oman left him battered physically and mentally.

Pierre Latour is second in stage nine's finish on Puy de Dôme. Sirotti photo.

Finishing exactly in the middle timewise, 3:03 behind race winner Jonas Vingegaard and 3:04 ahead of Morkov was Movistar’s Alex Aranburu. Alex finished in 52nd place on GC. Movistar was devastated on the first day as a major crash eliminated their race leader, and a true podium candidate, Enric Mas. You might recall that another top contender, Richard Carapaz (EF Education-EasyPost) was also eliminated on that day. Aranburu is a puncheur; if Mas hadn’t crashed out, Alex was a guy that would’ve worked for Mas on the non-mountain stages, and perhaps given his head on the several punchy stages that best suit his talents. But when a true contender goes down, it is often difficult for a team to recover.

Packfillers: extremely gifted athletes who are named to their teams for the greatest annual sporting event in the world, and even with all their talent, they still cannot match the superlative talents of those in the Top Ten of the GC. If you haven’t yet watched the Matej Mohorič video, this would be a good time to do so. Matej is not packfiller, yet he perfectly encapsulates the role of the riders in the peloton.

Post-Tour Withdrawal Syndrome (PTWS). PTWS is a documented medical issue that will get a French native out of work for the Blue Monday after the Tour closes. It is characterized by anxiety, a restless flipping of the channels in search of the day’s stage, and constant scrolling through a dozen websites (including but not limited to BikeRaceInfo.com) as one seeks the latest from the Tour. In years past, there was no cure but time. Thankfully, we have now have the Tour de France Femmes avec Zwift. The racing is wildly competitive and tres agressif. The teams are deep. It is truly outstanding racing, the women railing it every bit as hard as the guys, going every bit as deep. You’ll find a few favorites to root for, I promise. Watch it. You’ll see what I mean. Of course, what to do with your PTWS at the conclusion of the Women’s Tour on July 30th? White-knuckle it until the Glasgow World Championships begin on August 03, bien sûr!

Rider Safety. Since Henri Desgrange and Géo Lefèvre sent the riders off in the first Tour in 1903, the riders have been treated as disposable parts, barely worthy of consideration. You might not know that until Greg Lemond burst on the scene, riders were rarely booked into hotels that featured air conditioning even as the race took place in the heat of July as the tar melted on the roads. Road safety was an afterthought, even as riders went screaming down mountain descents, on roads that many had never before raced down, at speeds exceeding 60 mph/96.5 km/hr. (This year’s fastest speed was recorded by Rusty Woods (Israel-PremierTech), the winner of Stage 9. He hit 110 km/hr. That’s 68 mph.)

Woods wins stage nine. Sirotti photo

This improved safety is due to the hard work of Adam Hansen. Hansen is the Tour’s leading hardman. He completed 20 consecutive Grand Tours, riding every one until he chose not to race the 2018 Tour de France. Overall, he finished 26 of the 29 Grand Tours he started. He has won stages in the Vuelta and Giro. The man knows cycling and as an engineer, he understands safety. The same intensity and perseverance that marked his cycling career marks his work for rider safety. Hansen is the president of Cyclistes Professionnels Associes (CPA). That makes him the spokesman for the racers with the UCI and race organizers. His influence has been undeniable. He’s there to make sure that dangerous conditions are made as ‘not-dangerous’ as possible. He makes sure that weather protocols are put in place when necessary, even if it means the shortening of stages or the movement of official starts and finishes. For the first time in memory, we saw airbags in place at the outer margins of dangerous corners on descents. He pushes for tougher enforcement of the concussion protocol.

In short, he is the guy who looks out for the health and safety of the racers. Consider this – just 5 F1 drivers have died since 2000 either racing or practicing. Fabio Casartelli, Nicole Reinhart, Andrei Kivilev, Wouter Weylandt, Isaac Galvez, Michael Goolaerts, Suleiman Kangagi, Bjorg Lambrecht, Daan Myngheer, Bruno Neves, and Gino Mader have all died during high-level sanctioned competition since 1995. That’s 11 riders on bicycles. If I have missed someone, my sincere apologies. Please contact me on twitter @DStan58 so I can correct this piece. We must remember cycling’s fallen.

Cycling is a dangerous sport. Too often, it is a deadly sport, and through the work of Hansen and his team, we will not face a future where our finest athletes are treated as disposable commodities. Chapeau, Adam Hansen.

TV streaming. In the US, professional cycling is 100% a niche sport. Most of the people who watch are cyclists themselves. Some race, most ride for fitness and fun, but there is a definite physical connection to the bike. Lots of niche sports are like that—ski racing, track and field, equestrian—if you seek out a niche sport on TV, you probably participate now, in your youth, or your kids do the sport. A lot of people in the 1980s became cycling/Greg Lemond fans thanks to those epic John Tesh-hosted Tour de France shows on CBS Sports Saturday/Sunday during the Tour. People tuned in to catch “Sports Saturday” because that’s what we did at 3:30 pm EDT on the weekend. CBS showed a lot of niche sport back then, with enough boxing and car racing to keep the mainstream tuning in. Folks watched the cycling. They caught the drama and the suffering and the skill. They kept watching. They were generic sports fans who became cycling fans through free broadcast TV, an American hero, and sheer happenstance.

With the death of network broadcast TV and the explosion of streaming for every activity, there will never again be casual fans, for any niche sports, who become fans merely because of happenstance. You want cycling (or rugby, or Aussie Rules, or regular old boxing, et al.), you won’t find it by accident on free TV. You’ll find it on a streaming service because you went on a mission to find it. That, mes amis, is very bad news for the growth of cycling as a spectator sport in the US.

Baseball and football and basketball are part of US culture. Maybe you played some as a kid, maybe tossed the ball around with a parent, maybe you watched games on TV. Same in Europe with cycling. It is as much culture as sport. But to grow a spectator base without easy access to the sport that has no cultural underpinnings is just about impossible. A larger-than-life generational US talent might just get some Grand Tour level cycling on free TV. Maybe. That might drive people to seek out more content on streaming services. There’s been a massive shift in how content is delivered. I could be wrong. Let’s talk about this after the Tour in 2028, see how it all shakes out, eh?

Wout van Aert’s baby. Wout van Aert and his wife, Sarah de Bie, welcomed their second child, a son named Jerome on July 20th. Wout and Sarah also have a 2 year old son, George. What’s remarkable is that when Wout left the race on July 20th, there was little fanfare and no outcry. A family was having a baby, and a father’s place is with his wife and children when that happens. No big deal. Quite different from 1982, when Phil Anderson’s wife had to tuck her hair under her cap and impersonate a man merely to greet her husband at the hotel after a stage when he was holding the maillot jaune. Times change. Thank goodness.

Wout van Aert in stage 14, a few days before he left the Tour. Sirotti pnoto

In preview pieces and podcasts about this year’s Tour, I said that this year’s parcours was exceptional. Chapeau to Thierry Gouvenou for the thousands of kms he logged on a bike seat and a car to put together a parcours for the ages. All five French mountain ranges, and yet, it was a 22.4 km time trial that produced the most engaging Tour since 1985, ’86, and ’89. Every day was a gift. The racing was full gas from the drop of the flag. You cannot point to a single stage that didn’t grab you and hold you from start to finish. It was a spectacular way to spend three weeks in July. This year’s race was Ali-Frazier. Nadal-Federer. Tesla-Edison. Michigan-OSU. Evert-Navratilova.

Add Vingegaard vs. Pogačar to the list.

Vive le France! Vive le Tour!

David Stanley, like nearly all of us, has spent his life working and playing outdoors. He got a case of Melanoma as a result. Here's his telling of his beating that disease. And when you go out, please put on sunscreen.